The history of gin goes back hundreds of years—and to help explain where we took our reference and the role London Dry Gin has and will contrive to play in the category, we’re taking a trip back in time.

WHERE DID GIN COME FROM?

Enjoying a perfectly made gin serve might count as one of life’s simple pleasures, but the spirit itself has a rich and complex legacy that goes back centuries. Underlying the London Dry Gin that we enjoy today are numerous evolutions in tastes, styles, and distilling techniques. To show just how far the spirit has come, we’re following the history of gin all the way back to its earliest origins.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, long before London Dry Gin was ever in vogue, Britons enjoyed a juniper-led, citrus-backed spirit known as “the Water of Fruits.” One of the earliest-known formulas for the Water of Fruits dates to 1602, when it was printed in Sir Hugh Plat’s Delightes for Ladies (at the time, brewing and distilling were widely considered women’s work); the Worshipful Company of Distillers, meanwhile, published a distilling book in 1638 that featured several formulas of their own—all of which suggests that the Water of Fruits was a widespread and much-enjoyed beverage at the time.

At roughly the same time, genever, another juniper spirit, was being sipped merrily in Flanders and the Netherlands. Oude genever (old genever) was the spirit’s earliest iteration. Distilled from malted grain in small pot stills, the style was more akin to new-make whisky, and far from smooth. Juniper, as well as other herbs and spices, was a medicinal addition to the formula—it was thought to be a kidney tonic. Jonge genever (young genever), meanwhile, was a later evolution that arose when distilling techniques grew more refined and the spirit migrated from apothecaries to taverns. Lighter, and made primarily with grain instead of malt, it offered a subtler character and juniper flavour.

Though the Dutch-born William of Orange, who came to the British throne in 1688, is often credited with bringing genever to our fair shores, in reality we already had a taste for our Water of Fruits. We did borrow his terminology, however—from genever came the much catchier “gin.”

That brings us to the dawning of the 18th century, and the infamous Gin Craze. A few different factors helped stoke gin’s spiralling popularity. The Distilling Act of 1690 widely encouraged the production of grain-based spirits; in 1702, meanwhile, the newly anointed Queen Anne cancelled the charter that had granted the Worshipful Company of Distillers exclusive rights to produce gin in London and its environs.

That meant anyone could make gin—and they did. By the peak of the Gin Craze in the 1730s and 1740s, one in every four residences in certain parts of London was producing gin, and thousands of gin shops cropped up across the capital. The plenitude sounds appealing, but the gin of that era was often cheaply and badly made, potentially toxic, and even flavoured with turpentine, oil of vitriol and sulphuric acid instead of juniper—far from ideal, in other words. To help combat the debauchery, a series of Gin Acts, beginning in 1736, were passed by Parliament in an effort to cut down on illicit gin production (and soaring death rates).

Fast-forward several decades, after the worst ravages of the Gin Craze, to the era of Old Tom Gin. This distinctive style of gin first appeared on the scene in 1813, and is often referred to as “the missing link” between old-school Dutch genever and London Dry Gin. Old Tom Gin was notably sweet, and also darker in colour than today’s gin, as it was frequently barrel-aged (according to an 1823 dictionary of British slang, it took its name from the vessels in which it was commonly aged, which were nicknamed “Old Toms”).

From there, gin fortunes continued to improve. The invention of the Coffey still, or column still, in 1830—plus increasingly advanced distilling know-how—paved the way for the London Dry Gin we enjoy today. Distillers were able to load their pot stills with higher-quality base spirits than ever before, and produce gin that was more refined and elegant. Simultaneously, consumer tastes were shifting away from syrupy-sweet drinks and towards drier, more nuanced flavours. By the turn of the 20th century, London Dry Gin was the most popular style of gin for sipping and making cocktails.

WHY IS LONDON DRY GIN THE REFERENCE POINT?

Deliciously smooth, versatile, and balanced, London Dry Gin is the go-to in classic and contemporary cocktails.

There’s a reason why London Dry Gin has captured the imaginations (and the palates) of bartenders, distillers, and drinkers for over a century. Deliciously smooth and balanced, the style is the go-to in classic and contemporary cocktails—a versatile gin for all occasions.

In 2008, the European Union formalised the spirit’s definition in a way that guarantees the quality of its production: London Dry Gins must not contain any artificial ingredients, and cannot have any flavours or colourings added after the distillation process. Although the law allows for additional alcohol and even a tiny amount of sweetening to be added post-distillation, at Sipsmith we add nothing to our spirit except for water, which brings it to bottling strength.

When we set up shop in 2009, Sipsmith was London’s first copper distillery for nearly two hundred years. In the absence of a gin of truly uncompromising quality, our three passionate founders, Sam, Fairfax and Jared, set out to create a classic, handcrafted London Dry Gin, bringing the spirit back to its birthplace. From the first bottle, we have championed the belief that making gin by hand, with passion and immense skill, will lead to the most exceptional results. The Sipsmith team are at the heart of every drop, with a passion to inspire ever more people to discover and enjoy their classic quality London Dry Gin.

As our Master Distiller Jared Brown put it, “For our formula, we looked around for a reference point, a benchmark gin, but we quickly discovered that everyone had modernised and industrialised. So in the absence of a benchmark, we set out to make one ourselves.”

WHAT HAS COME FROM LONDON DRY GIN?

Today, we’re witnessing a new rise in contemporary gin styles that emphasise individual botanical characters.

When we started, there were just 12 distillers in the UK making gin; now, there are over 540, with 24 in London alone.

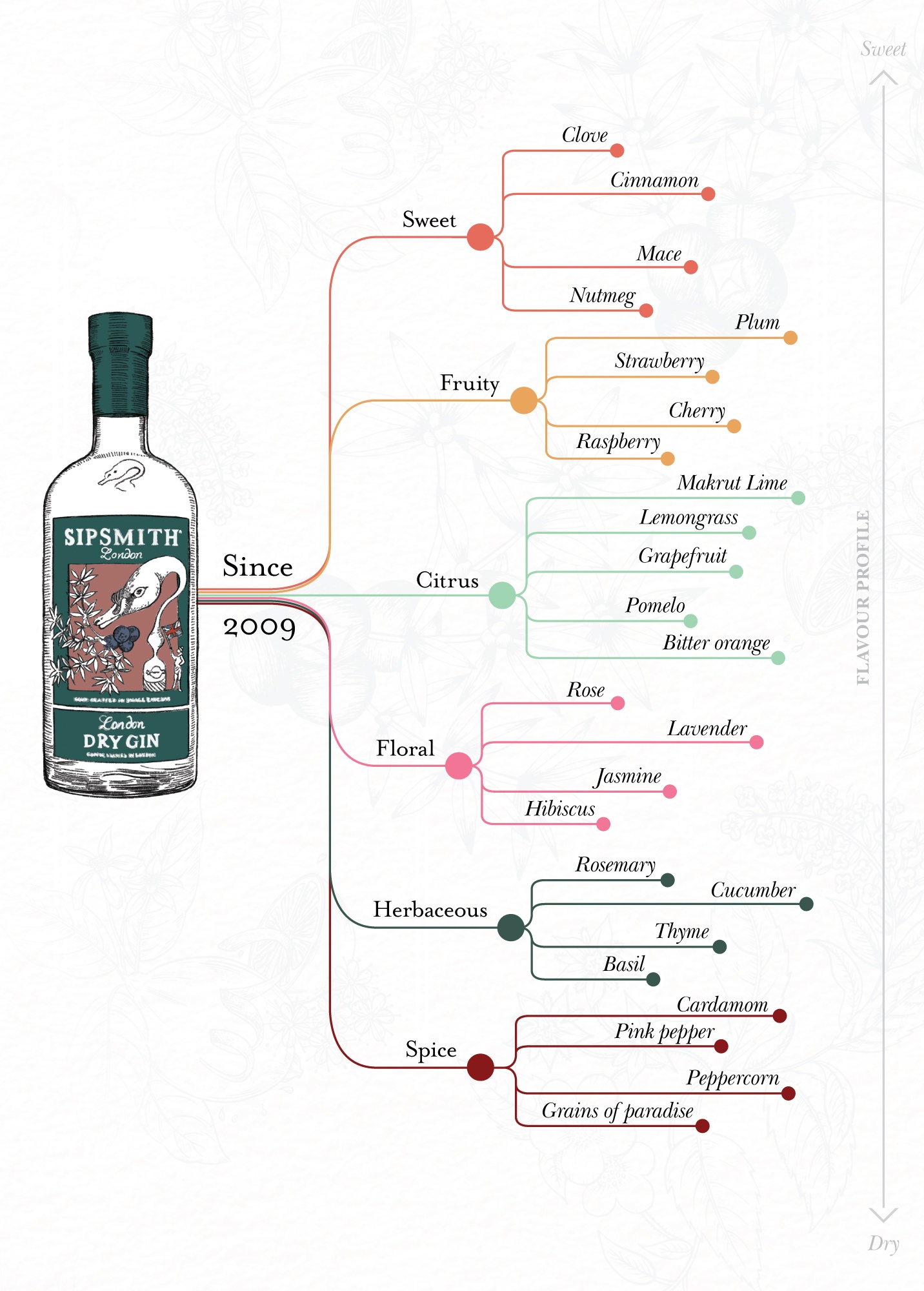

But gin’s story is still ongoing—and, following in the legacy of London Dry Gin, the spirit is continuing to evolve. Today, we’re witnessing a new rise in contemporary gin styles that emphasise individual botanical characters, from the herbaceous and floral to the fruity, spice-driven, or citric.

Taking our London Dry Gin as a backbone, our Sipping Society has allowed us to craft dozens of limited-edition distillations that play with gin’s creative potential. From Gingerbread Gin and Lemon Drizzle Gin to Strawberries & Cream Gin Liqueur and Fine Cordial Gin, these new styles dial up different elements, often far away from the classic London Dry Gin backbone of juniper, coriander, angelica, orris, cassia, liquorice, and citrus.

We believe that London Dry Gin will always play a pivotal role in the category and we hope that our recipe, with its authentic style, rooted in history, will continue to be a useful reference point to help gin lovers navigate this fast-growing category.